Successful EU policies on the renewable energy communities front have started bearing fruit. Throughout the EU, more than 9,000 communities have been developed, serving as a beacon of decentralised energy and smart cities. However, the road to net-zero communities is still long, as heating, cooling and agroforestry are ‘thorns’ that stand in the way of full-scale decarbonisation at a community level. Could it be that one of the ‘thorns’ can become a ‘rose’ for the energy transition?

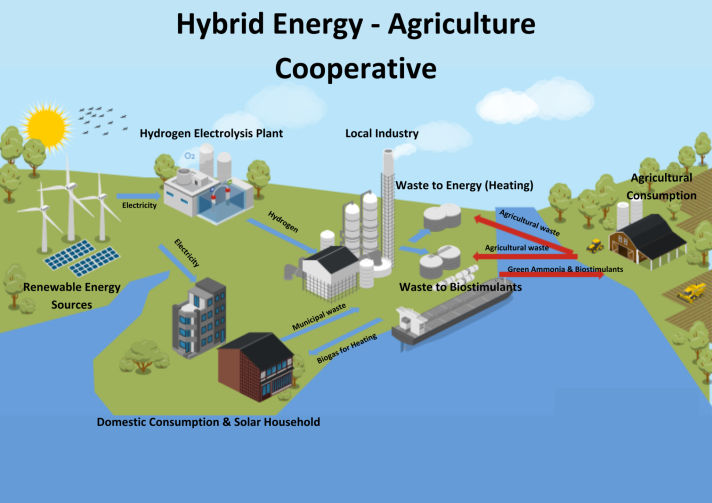

The concept of renewable energy communities and cooperatives (RECs) is hardly something new in the EU energy policy landscape. Some of the characteristics of RECs, which can be defined as renewable energy clusters characterised by several different energy sources, flexibility, interconnectivity and bi-directionality of energy flows, can be found in European projects dating back to 2007. However, it was not until 2018 that the EU Renewable Energy Directive (RED II) officially introduced the concept and started the spiralling trend of their deployment across most EU member states. This directive included all the regulatory and legal requirements to consider an entity as a REC, whilst the Internal Energy Market Directive (IEMD) focused on the role of the energy prosumer, their means of compensation and financial mechanisms to support RECs. The aforementioned frameworks, however, maintain challenges with regards to bioenergy communities. Unleashing the untapped potential of bioenergy in communities is of uttermost importance to decarbonise hard to abate sectors, such as heating, cooling and heavy transport, but, most of all, it opens the door to the development of hybrid cooperatives of energy and agriculture. An example of a hybrid energy-agriculture cooperative can be seen in Figure 1. Its benefits span across waste management, shorter supply chains and urban food security, as well as high financial and societal value.

Waste management powerhouses

Despite the important strides that the EU has made with regards to waste management, there is still more than 50% of municipal waste that is not valorised or repurposed, whilst 64% of packaging waste is landfilled. Both can function as excellent sources of biomass. Processes involving gasification and pyrolysis can be used to develop biogas or biochar, depending on the context, whereas fermentative processes can lead to formulation of biohydrogen or biostimulants. The aforementioned can be used as forms of district or farm heating or be provided to farmers to reduce the costs of fertilisers and soil amendments. Most importantly, though, it leads to minimising waste, which accounts for 10% of greenhouse gas emissions.

The benefits of introducing agriculture in a bioenergy cooperative

As mentioned, several of the end-products of biomass treatment are highly relevant to agriculture, such as soil amendments and biostimulants. Within the urban realm, these can prove to be immensely useful for the development of ‘pocket parks’ and ‘urban food forests’. The former have high potential of reducing heat stress in European cities that need it the most, while the latter can enhance food security and facilitate access to food. This is consistent with the strive of the EU as part of Food 2030 to promote short supply chains, local production and consumption. It can also be combined with education activities, where students can learn how to grow their own urban food forests, thus increasing community resilience.

Economic and societal value

Depending on the business model or the approach a local community will opt for, biomass providers can generate revenue. These include municipal authorities providing waste, farmers that might grow energy crops in arid and semi-arid environments, or farmers and forest authorities selling agricultural waste and residue. On the other hand, choosing a project of high societal value, the bioenergy produced or the agrifood products generated can be distributed to the most vulnerable communities. This has even higher value, considering that during the energy crisis, as well as the inflation spiralling episodes, the most vulnerable communities faced their most dire reverberations.

Barriers and the way forward

However, there are several obstacles in achieving such a harmonious co-existence of agriculture and energy within a cooperative.

- Financial barriers: Some of the equipment required for biomass treatment, especially with regards to energy, can be costly. Public and private financial mechanisms need to be adapted to the context of such a structure and also local communities should become aware of how to access funds and utilise them effectively for the development of an economically well-functioning cooperative.

- Social acceptance: A large part of such a project will require substantial behavioural shifts among all societal groups. Establishing the cooperative, thus, will require effort and many citizens might focus on the short-term gains, which will be few, and will not see the ample long-term advantages. Communicating effectively the project and its outcomes, but also performing consultations with local communities, rigorous stakeholder engagement map and conversion of them to a concrete plan of action will be very important. Organisations that will function as the ‘glue’ to all of these activities will be paramount.

- Technical obstacles: Issues such as arranging logistics and supply chains as well as deciding on the business model, means of compensation or choice of a non-profit socially beneficial plan are still unclear. Pilot projects will be of uttermost importance to lay the ground, as their results will be a roadmap for other communities that will want to follow. A project with similarities is BECoop, whose results can function as a starting point for a hybrid energy-agriculture cooperative.

Recommended links

- https://www.rescoop.eu/

- https://www.becoop-project.eu/

- https://rural-energy-community-hub.ec.europa.eu/index_en

- https://energy-cities.eu/publication/how-local-authorities-can-encourage-citizen-participation-in-energy-transitions/

About the author

Dimitris Symeonidis is an energy policy visionary and geopolitical risk advisor, with a track record of working with stakeholders spanning the public, private and third sectors. He works as an energy market analyst for VaasaETT, specialised in regulatory framework reforms. He is also a project manager of Afforest for Future, working on research, innovation, communication and advocacy in transformation into a regenerative economy in the Global South. He is policy lead at YES-Europe, mobilising youth in Europe and beyond in becoming leaders in the energy transition.

Disclaimer: This article is a contribution from a partner. All rights reserved.

Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use that might be made of the information in the article. The opinions expressed are those of the author(s) only and should not be considered as representative of the European Commission’s official position.

Details

- Publication date

- 28 March 2024

- Author

- European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency